The Elusive Nature of Matter: A Philosophical Inquiry

The Elusive Nature of Matter: A Philosophical Inquiry

Matter, the stuff of the physical world, has been a central concern of philosophy for millennia. From ancient Greek atomism to modern quantum mechanics, philosophers and scientists have sought to understand the true nature of matter: What is it? What are its properties? How does it relate to consciousness and the mind? And can we ever truly know it? The question about the real nature of matter is related not only to metaphysics, but also to the frontiers of knowledge, perception, and scientific explanation of the human mind.

The philosophical investigation into matter can be done from many sides, and the more we come to understand it scientifically, the more elusive it seems. At first glance, matter seems to be real stuff: everything in the universe-from the tiny particles to vast galaxies-is composed of or made up of matter. However, the deeper we investigate into both philosophical and scientific inquiries, the more matter tends to dissolve into paradoxes, complexities, and uncertainties.

1. **Ancient Greek Atomism: The First Step to Understanding Matter**

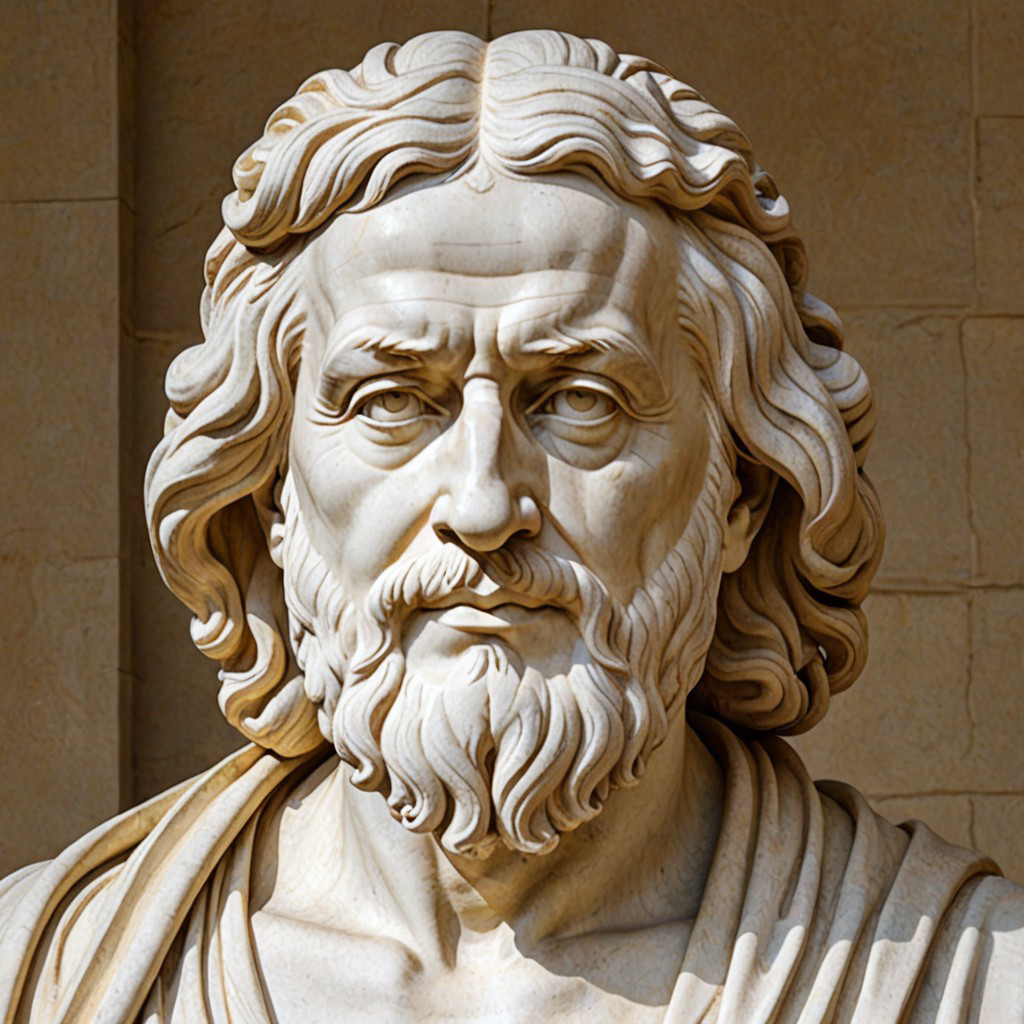

The history of Western thought about matter can be dated back to ancient Greece and the Pre-Socratic philosophers. It was **Leucippus** and **Democritus** who suggested that matter is composed of small indivisible particles called atoms. According to their theory, the properties of objects in the world were determined by the arrangement and motion of these atoms. This early atomism provided some sort of conceptual framework for thinking about matter, as being made up with the fundamental, unchangeable units that would succeed in influencing the development to modern science.

In a philosophical sense, **Democritus'** atomism introduced an important distinction between the *phenomenal* world — that is, the world of appearances — and the *noumenal* world — or the world of reality, as it exists independently of human perception. For Democritus, the world we experience is but an appearance of the interaction of these minute, insensible particles. This dichotomy between appearance and reality presages later philosophical worries about how we know the world and whether our perceptions can ever disclose the nature of reality.

2. **Aristotle: Matter as Potentiality and Actuality**

In contrast to the atomism of Democritus, **Aristotle** provided a more complicated and holistic account of matter. For Aristotle, matter was not made of indivisible atoms but was a substance that existed in a state of potentiality. Matter, in his view, was what underpinned change and motion. He introduced the distinction between *hyle* (matter) and *morphe* (form), suggesting that everything in the natural world was a combination of these two principles.

For Aristotle, matter had to be understood as in the state of becoming and therefore could never be constant, stable, or static. The world around us was one dynamic process whereby potentialities through the form were always made actual. This notion of matter as a kind of possibility had an effect on how medieval and early modern substance theories were presented- theories tied to notions of change and transformation in nature. In philosophical terms, this view underlines the constant tension between stability and change-a theme which is still at the core of modern metaphysics.

3. **Modern Science: The Elusive Nature of Matter

In the modern era, the scientific revolution changed our understanding of matter. With the work of **Isaac Newton**, among others, matter came to be seen as composed of discrete particles that combined in fixed laws of motion and gravitation. According to the classical view of matter, matter was thought to be composed of small particles with definite properties such as mass, volume, and location.

However, as physics evolved, the picture of matter began to get more and more elusive. With the dawn of **quantum mechanics** in the 20th century, it turned out that matter at very small distances behaves in opposition to our classical understanding of it. For example, the so-called *double-slit experiment* exhibited that such particles as electrons may express both particle-like and wave-like behavior, depending on an act of measurement. Here, a new term, namely, *wave-particle duality*, appeared with the meaning that the matter became radically indeterminate in its nature.

In addition, quantum theory gave us the concept of **uncertainty**. **Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle** says that it is impossible to measure exactly both the position and momentum of a particle at the same time. This has deeply philosophical implications: If we cannot know the exact nature of matter, is it in fact "real" as we think? Or does it only become "real" when we observe it? The quantum view is that maybe matter does not have an independent state, which is a challenge to the very nature of reality and pushes us toward a more subjective understanding of the world.

4. **Philosophy and the Problem of Substance**

The question of what matter actually *is* leads to the classical philosophical problem of **substance**. What is the fundamental stuff that constitutes the universe? Various answers have been offered by philosophers, some claiming matter is a basic substance, while others hold that it is an abstraction or a way to describe the properties of things.

René Descartes:, for instance, is known to have divided the universe into two substances: res extensa-which translates as matter, or extended substance-and res cogitans, a Latin phrase which means mind or thinking substance. To him, matter was the thing to be subjected to measure and understanding through scientific investigation, while the mind was an independent, nonmaterial substance. This dualism engendered many debates both in metaphysics and the philosophy of the mind.

On the other hand, **Spinoza** was a 17th-century philosopher who rejected dualism and adopted a monistic theory of substance. He postulated that there is only one substance in the universe, which he referred to as **God or Nature**. For Spinoza, matter and mind were not independent entities but manifestations of an infinite substance. His theory is the forerunner of the modern holistic and ecological view of the universe in which the universe and all that is part of it is seen as interrelated.

More recently, the dominant philosophical position of **materialism** holds that everything in the world is ultimately made up of matter. Yet, even within materialism, the relationship between matter and consciousness is difficult to explain. **Neuroscientific materialists** further argue that consciousness can be fully explained by the interactions of physical matter in the brain. However, this view is still highly debated, with some philosophers, such as **David Chalmers**, arguing that consciousness might be something irreducible, not fully explainable by physical processes.

5. **Matter, Perception, and Reality**

The elusiveness of matter is not only a scientific or metaphysical question but also one about human perception. What do we actually "know" about the world around us? There, philosophers like **Immanuel Kant** thought that we can never actually know "things in themselves" (*noumena*), only the world as it appears to us (*phenomena*). For Kant, this means that our experience of matter is always filtered by our sensory faculties and conceptual categories, so what we call "matter" will always be mediated by the human perception and cognition process.

In this sense, the very concept of "matter" may be bound up with the limitations of human consciousness. The *real* nature of matter, if it exists independent of our perception, remains forever out of reach, leaving us to navigate the world with only partial, and often flawed, understandings.

6. **The Elusiveness of Matter in Contemporary Thought**

The nature of matter has continued, today, to inspire philosophical reflection. The replacement of quantum field theory, in which particles are not considered discrete objects but excitations in underlying fields, further complicated our conception of matter. Gone is the distinction between "particles" and "waves" in favor of a fluid, dynamic understanding of reality in which matter is no longer a substance that can be pinned down.

Furthermore, various philosophical investigations into **emergentism** indicate that what we refer to as "matter" may not reduce to one single, fundamental substance but instead could emerge from complex interactions between simpler elements. For instance, the sophisticated behaviors of matter in biological organisms or social systems can be understood as emerging from the interaction of fundamental particles or physical laws but not reducible to them.

Conclusion: The Mystery of Matter

It is in that way a philosophical investigation into the nature of matter-a richly evolving quest from ancient atomism to today's quantum physics-that does justice to the elusiveness of the question about the limits that human knowledge will have, the part played by perception in shaping reality, and the nature of the universe in the ultimate analysis. Be it basic substance, a conglomacy of interacting forces, or an emergent property of complex systems, one thing about matter remains clear: it is not easily pinned down. It is both an intellectual and an existential mystery that puzzles the mind, inspires wonder, and continuously reshapes our understanding of the world.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment